Somewhere in the bustling town of Bonwire in Ghana, a folk story is being passed on from one generation of artists to the next. Draped in bedazzling striped clothing, the custodians of a long venerated art are recounting the story of Nana Koragu and Nana Ameyaw returning to their village on the fateful day when they came across a spiderweb. Struck by its intricate design, the two friends (in some traditions, brothers), decided to take the web back to their homes. However, when they took the web off the banana tree it broke and lost its design. Yet, fate smiled upon the weavers, and their return to the jungle the following day was rewarded with the sight of another web in the process of being woven. As they watched in awe, Ananse, a large, magical, yellow and black spider weaved the web with an enchanting dance that used techniques like twisting, turning, and dipping. Armed with this newfound knowledge, the two returned home to make textile history…

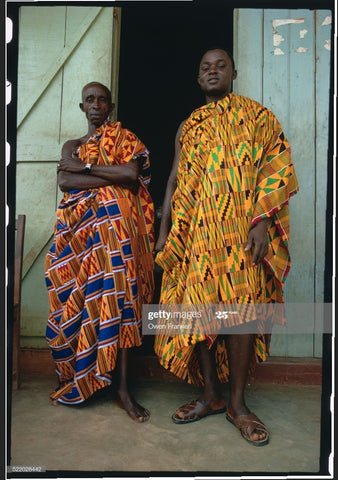

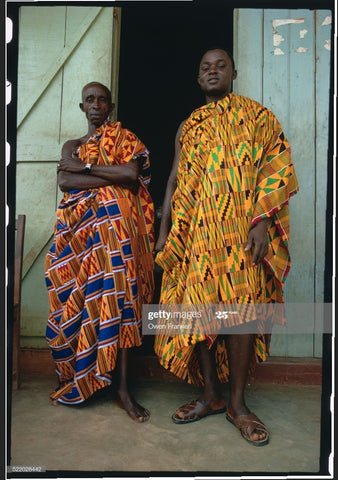

Two Ashanti kente weavers in Bonwire, Ghana. Bonwire remains widely acknowledged as the home of kente weaving even today.

Two Ashanti kente weavers in Bonwire, Ghana. Bonwire remains widely acknowledged as the home of kente weaving even today.

Called nwentoma by the ethnic Akan people of Ashanti, kente cloth is perhaps the best known textile from Africa today. A veritable icon of West African cultural heritage and most notably associated with the Akan and the Ewe peoples, kente has traditionally been held dear for its symbolism and aesthetic, both of which intertwine in uniquely fascinating ways.

Itself a microcosm of the rich culture that birthed it, nwentoma literally means “woven cloth”, a nod to the stripweave method that it represents. Traditionally handspun, stripweaving has been widely practiced in West Africa for hundreds of years, where practitioners have handwoven narrow strips of different cloths together into a finished garment, an art of which kente is the most ubiquitous global ambassador. Kente is traditionally woven in long narrow strips with brightly coloured silk or cotton yarns on a traditional narrow loom called a Nsadua Kofi, a box-like wooden structure in which the weaver sits to practice her art. It usually incorporates weft designs such that, woven together, the completed cloth has a distinctive patchwork appearance.

Two Ashanti noblemen in Kumasi, Ghana, wearing elaborately woven kente garments at a celebration for the new Asantehene, the Ashanti chief. Kente clothing has a large ceremonial role to play among the Ashanti people.

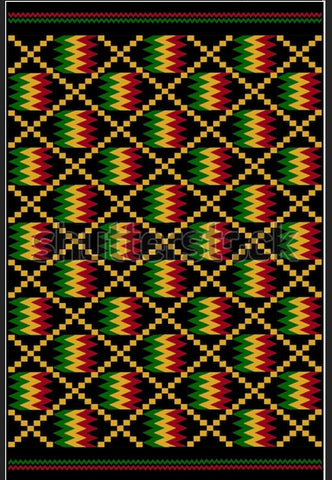

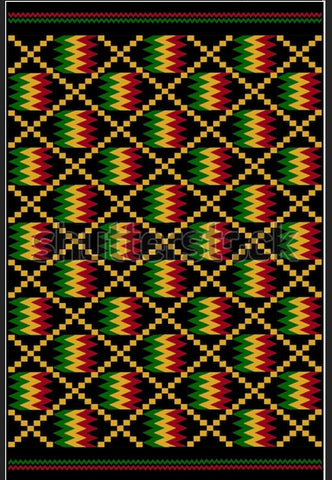

The art of Kente weaving varies widely in design and complexity and the colours and patterns associated with it often have deep meaning for the Akan and Ewe peoples. It is an expression of poetry using the woven motifs and their colours as a means of expression.

- The simplest of these is the Ahwepan or Hweepan kente pattern, which has no design associated with it, hence “hwee” signifying nothing.

- The Akyem kente pattern, named after a local bird, is noted for its colourful nature.

- The Faprenu kente pattern has two (prenu) warp sheets woven together with one weft sheet, resulting in its incredible strength.

- Adwin kente patterns, named for skill, involve intricate designs.

- The adwinasa pattern has been particularly notable. It literally means the exhaustion of skill, representing a magnum opus into which the creator has expended everything they have.

Tradition meets modernity in this expressive adwinasa patterned pair of canvas sneakers and handbag.

Kente clothing has long embodied and personified lyrical motifs. The Afiadeke Mefa o pattern is a reminder to be grateful for what one has, just as the Lorlofukpekpe pattern is a doleful and sobering reminder that things may not always be as imagined, and disappointment, from time to time, is inevitable for all. Apart from the motifs, the colours have their own symbolism. Blue typically expresses love, green growth and energy, yellow or gold evoke wealth and royalty, a reminder of vast gold and riches of the Akan people. Black is traditionally used to evoke death or aging, white goodness and victory, and red violence and anger. Like much of African culture, kente clothing represents dynamism and rhythm, where cultural communication comes alive with the wearer’s active participation. Famous modern kente masterpieces include Obaakofo mmu man, or “one man does not rule a nation”.

Originally titled Fathia Fata Nkrumah”, in honour of former president of Ghana Kwame Nkrumah and his wife Fathia, this pattern was later renamed Obaakofo mmu man.

Proverbs have always been an intimate look inside a community’s culture, values, and intellectual processes. When these are expressed as dynamic and artistic stylizations, they bring a secondary layer of understanding and expression to the community, and are a priceless addition to global fashion and cultural heritage. Kente clothing represents a pinnacle of artistic achievement and continues to be widely worn both traditionally, and in more modern styles such as academic stoles in the United States. The world is indebted to the creativity and resilience of the people of West Africa, who have ensured that this fine art is not a quaint relic of the past, but a living, thriving cultural institution that continues to inspire and amaze.

The 1st of August 1834 is a special day in the hearts and minds of Africans, and the African diaspora. Emancipation Day is celebrated for the final abolition of slavery in the British Colonies, and celebrations in Ghana frequently witness beautiful kente dresses like the one pictured above, adorning a young girl in Assim Manso, Central Ghana.

The 1st of August 1834 is a special day in the hearts and minds of Africans, and the African diaspora. Emancipation Day is celebrated for the final abolition of slavery in the British Colonies, and celebrations in Ghana frequently witness beautiful kente dresses like the one pictured above, adorning a young girl in Assim Manso, Central Ghana.

The story of Kente is one that is fundamentally inseparable from the people that created it, a story of riches both, cultural and material, pride, and resilience. For as the people of West Africa withstood the ravages of colonialism, warfare and strife to emerge stronger, so too has their art, embracing the modern world while strengthening its roots at the same time. Our Ghana sourcing specialist is always on the lookout for whatever might best serve your needs, and at Culture Kraze, we are both humbled and honoured to be a small part of the evolving story of kente.

References:

- Lewis, George H. “CULTURAL COMMUNICATION IN BLACK WEST AFRICA: KENTE CLOTH AND MAMMY WAGONS.” Michigan Sociological Review, no. 5, 1978, pp. 22–32. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/44952584.

- Smith, Shea Clark. “Kente Cloth Motifs.” African Arts, vol. 9, no. 1, 1975, pp. 36–39. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/3334979.

- Adjaye, Joseph K., and Adrianne R. Andrews, editors. Language, Rhythm, and Sound: Black Popular Cultures into the Twenty-First Century. University of Pittsburgh Press, 1997. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt7zw866.

- http://www.jstor.org/stable/3334979https://www.researchgate.net/figure/The-traditional-loom-The-traditional-or-Kente-loom-as-shown-in-Fig-1-consists-of-four_fig2_279298672.

- https://touringghana.com/bonwire-kente-weaving-village/.

- https://www.culturesofwestafrica.com/the-weaver/.

- https://www.thoughtco.com/what-is-kente-cloth-43303.

- https://africa.si.edu/exhibits/kente/strips.htm.

Two Ashanti kente weavers in Bonwire, Ghana. Bonwire remains widely acknowledged as the home of kente weaving even today.

Two Ashanti kente weavers in Bonwire, Ghana. Bonwire remains widely acknowledged as the home of kente weaving even today.

The 1st of August 1834 is a special day in the hearts and minds of Africans, and the African diaspora. Emancipation Day is celebrated for the final abolition of slavery in the British Colonies, and celebrations in Ghana frequently witness beautiful kente dresses like the one pictured above, adorning a young girl in Assim Manso, Central Ghana.

The 1st of August 1834 is a special day in the hearts and minds of Africans, and the African diaspora. Emancipation Day is celebrated for the final abolition of slavery in the British Colonies, and celebrations in Ghana frequently witness beautiful kente dresses like the one pictured above, adorning a young girl in Assim Manso, Central Ghana.

Leave a comment